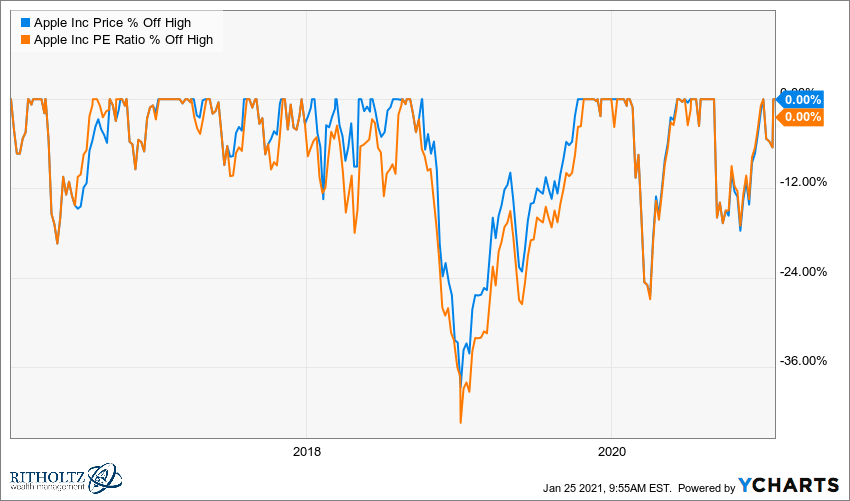

There was a moment in the fourth quarter of 2018 where shares of Apple fell 38 percent in a matter of just a few weeks. Nothing much had fundamentally changed, but the stock market had been hit by a wave of fear that the Fed would go “too far, too fast” in normalizing interest rates and that China would retaliate against Apple in the Trade War™.

And during that brutal bear market, in which the S&P 500 fell half as much as Apple – roughly 20 percent – the Greatest Company on Earth‘s stock actually got momentarily cheap. Its price/earnings ratio (on trailing twelve months’ earnings) fell by more than its share price, a drop of 43 percent from the high in September. So investors had implicitly (and very temporarily) decided that Apple’s valuation should only be about half of what it was given the great fears of that moment in time.

This was one of those rare moments where Apple had gotten inexpensive. Since then, the stock has sold at an above-market multiple ever after. And with good reason – there isn’t another company like it and there probably never will be. So if you want in, it’s a one-way situation. And if you don’t, that’s fine too. But the valuation is the valuation and there is no good reason for why investors should expect “a bargain” for Apple shares anytime soon.

If this sounds very intuitive – and it is intuitive – it’s also, believe it or not, slightly controversial among certain investors. There is a school of thought out there, and it’s a school that continues to accumulate L’s year after year, that it is better to buy a piece of shit company in a dying industry if it sells at a discount rather than to buy a wonderful company at a premium. I’m not saying this approach won’t work periodically, but I remain unmoved by all of the arguments where this is the sort of thing investors should strive to do in all the time. Why should they? Because a textbook from the 1930’s said so, or some such nonsensical reason.

Practitioners of this ancient art of dumpster diving hold up Warren Buffett as their patron saint; the living embodiment of their investment philosophy and all its haughty ideals. Which is absolutely hilarious because Buffett hasn’t been pursuing those types of investments for five decades. He’s been buying growth companies in growing industries and paying a premium almost every time as he’s put a position on. In the rare cases that he’s attempted to buy “cheap” stocks, he’s ended up with absolute lemons like IBM and Wells Fargo, which have all been eventually sold after losses and a bit of reputational bruising. Buffett may sing from the value investing hymn book from time to time, but the night before services he’s at the billiards hall with the rest of us. Berkshire has spent the past five years as Apple’s largest shareholder, with its P/E ratio soaring by 300 percent during their ownership. They never so much as flinched.

The success of Apple’s stock is not a repudiation of value investing because many of the investors who’d originally been excited about the stock began to buy when it was selling at a discount to the S&P 500’s PE ratio in the early twenty teens. Notable value investors, like Berkshire and David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital “rediscovered” Apple first, before it became cool again.

That wasn’t the hard part – everyone could see that it was inexpensive. The hard part was staying with the trade as the stock began to trade at a premium. That’s where all the really big gains came from. Can you buy a stock for one reason (valuation) and then hold on when that reason goes away but new reasons (renewed growth) start to surface?

Can I show you PayPal?

PayPal had been a public company during the first dot com boom and then got swallowed up by eBay in a merger that made tons of sense back in 2002 – PayPal’s main raison d’être was enabling buyers and sellers on the platform to execute transactions. But then, circa 2014, some activists looked at the amazing growth of PayPal as a business unit within eBay and forcefully demanded a spin-off. Carl Icahn was right about this while some of eBay’s technology industry board members and advisors who’d pushed back were actually wrong. PayPal came public in July of 2015 and for six and a half years has become one of the great growth stories of our time.

Wall Street’s analysts were mostly uninterested in PayPal because of, well, you guessed it – the valuation. Read the initiations of coverage – the “experts” covering the space liked the PayPal story but panned the stock because of its price. They were more bullish on eBay, which was already in its red dwarf phase. Why? Again, valuation.

People who imaginations usually gravitate toward employment at Walt Disney, not Merrill Lynch. The ability to think creatively and act boldly might be the last edge left in the stock market.

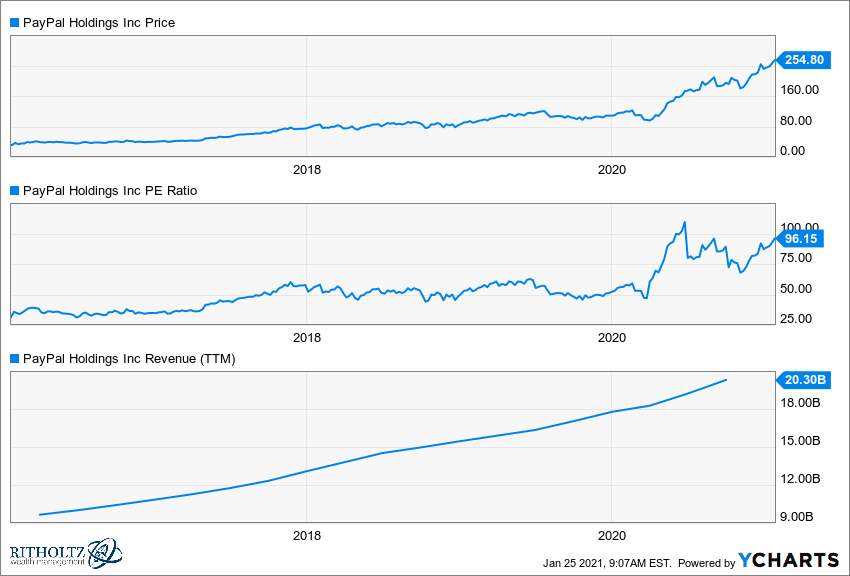

But what I really want to tell you is that never, during this entire run-up to a $300 billion market cap, has PayPal ever been “inexpensive.” Never. You know why? Because markets aren’t stupid. And often, stocks become “expensive” on traditional measures for good reason. The popularity contest isn’t always wrong.

Below I am showing you PayPal’s share price versus its PE ratio versus its revenue growth. While people who care about bullshit measures like PE ratios were sitting in Wells Fargo and other somnambulant “traditional” banks, PayPal was becoming one of the most important financial services companies of the 21st century. The bulls, having paid up for the stock consistently since the spin-off, were right all along:

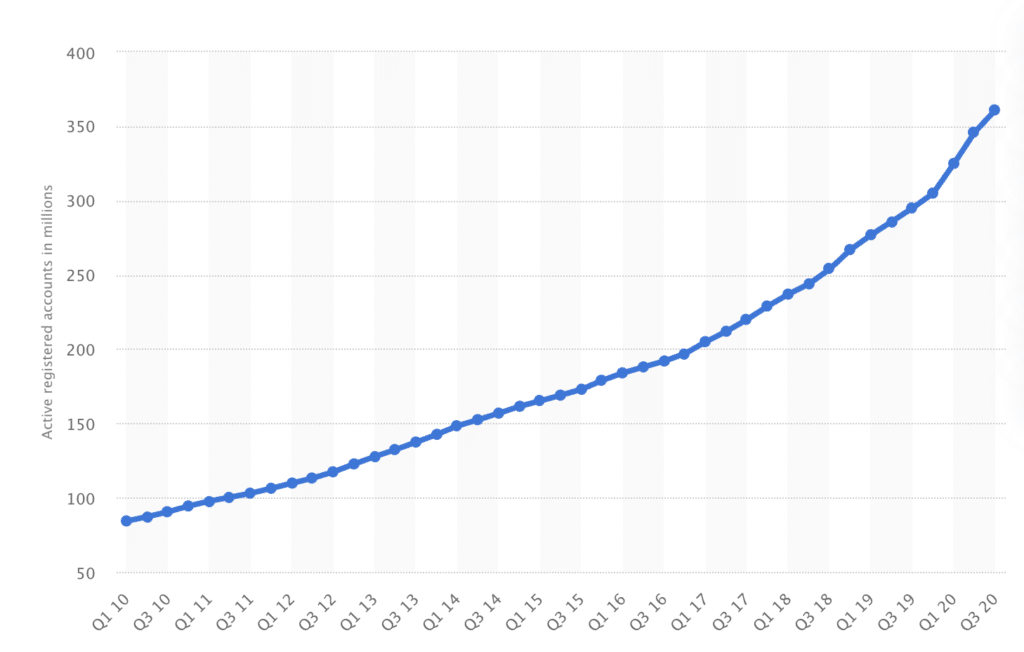

Here’s PayPal’s active user base through 2020. No one could have predicted the pandemic-related boom in online / contactless payments, but no one would have had to. The growth began long before coronavirus.

Tell me why an asset-lite, cutting edge financial services company with 350 million plus active users – young and sticky users – wouldn’t deserve a premium valuation?

People understood that this growth rate could (not would, but could) someday justify paying 30, 40 and 50 times earnings for PayPal shares. That risk paid off. PayPal’s stock has returned an annualized 41 percent since coming public in 2015, which is four times the annual return for the S&P 500.

Let me finish by clarifying what I am saying versus what I’m not.

I am saying that just because you own a calculator and can observe that some stocks are more expensive than others, that doesn’t mean the best course of action is to buy the more inexpensive one. Others have observed the same disparities in price that you have. You’re not Ferdinand f***ing Magellan discovering something new. Kneejerk reactions to “expensive” valuations have been a massive money-loser, especially in markets where brand, innovation and scale matter most.

I am not saying that valuation is irrelevant and investors should just pay any price for any stock. Snarky, cynical reductio ad absurdum arguments are an even bigger money-loser.

If you’ve only read and absorbed books from one investing discipline and you’ve anchored all of your opinions on that, then you can’t understand the way things are and have been. If you’ve been open-minded, however, you can.

(full disclosure, I own shares in both Apple and PayPal)