This weekend, Nvidia is in the news because of a Wall Street Journal breaking story about their impending purchase of British chip designer Arm Holdings from Softbank. By acquiring Arm for roughly $40 billion, Nvidia catapults itself into a leading position in the smartphone market – an enormous opportunity that represents a whole new chapter for the company if they can pull it off.

I want to take this opportunity to relay one of the most important truths I’ve ever learned about the stock market. I’ll use Nvidia as a jumping off point, but what I’m about to share with you will prove valuable for all of the investing you’ll do for the rest of your life.

In the summer of 2015, growth investors began to buy shares in Nvidia, which was becoming well-known for its prowess in using graphical processing units or GPUs (the semiconductor chips found in video game consoles) for other non-linear computing processes, like AI, machine learning, autonomous driving, cloud computing, etc. The stock broke above resistance at $50 per share and then never looked back. In June of that year, NVDA sold for a multiple of 30x trailing twelve months’ (TTM) earnings per share.

At the same time, value investors were taking an interest in Intel, a larger, more well-known semiconductor stock with Dow Jones Industrial Average component bona fides and a long history as a household name in the sector. Intel was selling at 15 times trailing twelve month’s earnings. Compared to Nvidia, it looked like a bargain. It even had a dividend.

Now here’s where the trouble comes in. In the technology sector, you aren’t rewarded for focusing on valuation to the degree you’re rewarded for buying growth potential. The multiple on trailing earnings for a technology stock is probably the very worst thing you could pay attention to because it tells you absolutely nothing about the company’s vision for the future, and where they may fit into that future. It just so happened that Intel didn’t have a useful vision for the future or a good roadmap for building that future out. Nvidia did.

And in this way, the large valuation disparity between these two semiconductor giants ended up being completely justified as the ensuing five years unfolded. Which is why there are no famous value investors in the tech sector. Which is why “bargains” and “innovation” are rarely found together in the wilds of the Nasdaq. It’s why the shorthand of earnings multiples and book values and such are completely irrelevant when your fellow investors are buying and selling based on what will happen, not what has happened already or what has been happening over time.

It makes perfect sense for rational investors to scrutinize valuations based on backward-looking fundamental metrics in a space like consumer staples. It’s highly likely that 2021’s demand for Coca-Cola or Kleenex will look similar to 2020’s or 2019’s. There’s room for the company to sell a little more or a little less, and operations can get more or less efficient, and then you decide what you’d like to pay for this sort of reliable, consistent cash flow and you buy it. The idea that you could do this with the stocks of innovative companies that are literally changing the world is hilariously childish.

And yet you hear all the time about how this or that tech stock is cheap versus its peers. As though the market’s hundreds of millions of participants do not themselves possess a calculator to sort that valuation disparity out for themselves. Did it ever occur to you that these valuation disparities might be justified by what happens in the future? Is it reasonable to be so dismissive of the price-setting activity of the crowd that your kneejerk reaction is to always prefer the “cheaper” stock, regardless of its prospects? Or to automatically denigrate the stock that other investors are paying up for? Are they always wrong or reckless? Is every burst of enthusiasm the onset of a bubble?

In the technology sector, and among the chip giants specifically, the exact opposite has been the case. Paying up for innovation versus prioritizing low multiples for historic market share has been the only path to prosperity.

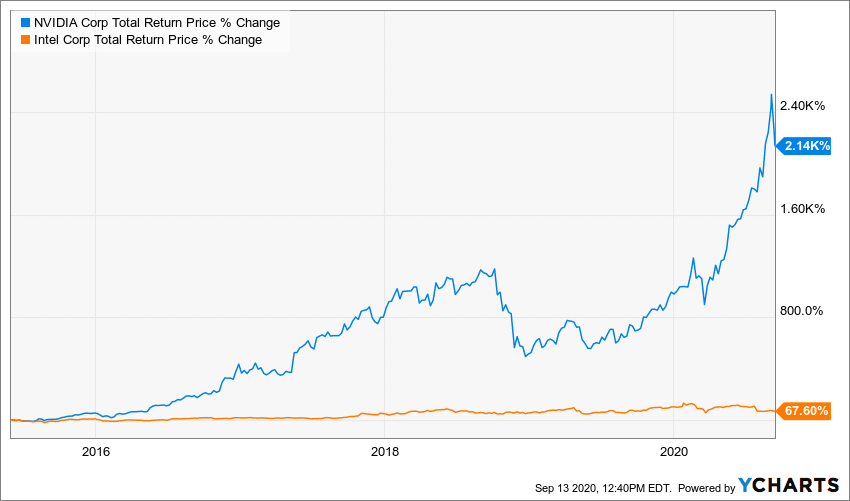

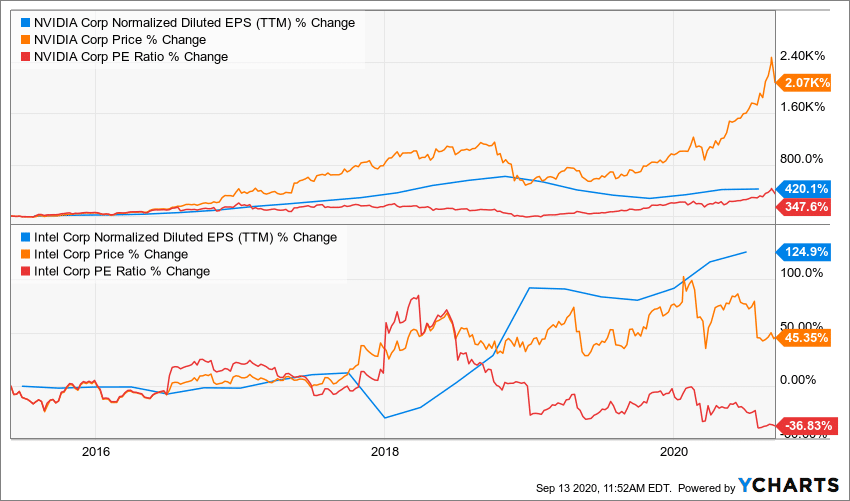

Let’s take a look at how this has played out with Intel and Nvidia (using YCharts, which you can check out here):

First, let’s look at the percentage change over five years in three metrics: Earnings per share growth (blue), the price return of the stocks (orange) and the TTM PE ratios (red) for each.

Nvidia’s 2,000% price return will be the first thing that jumps out at you in the chart above. Intel’s share price is up a more modest 45%. Nvidia’s annual earnings have grown at over 400% during this time frame, almost quadruple the earnings growth for Intel. Which means that paying double the PE ratio for Nvidia in the summer of 2015 has worked out splendidly for investors who paid more attention to the innovation and less to the valuation based on then-current fundamentals.

In fact, Nvidia’s PE multiple (in red) has grown in concert with the actual earnings themselves, giving shareholders an even more powerful tailwind than the earnings growth alone would have provided – stocks that are seen as winners often get this increasing benefit of the doubt as they continually exceed earlier expectations, which is one of the most frustrating aspects of being a value investor in modern times. It’s double-counting! You may say that this premise is obscene or unwarranted or even unfair, but I can assure you that the money is real. And not only did Nvidia shareholders get rewarded with a growing PE multiple – Intel shareholders were punished with a declining one! Intel’s PE ratio has spent the last five years shrinking by almost 40% as the market’s participants have gradually penalized the company’s ability to innovate and execute in the semiconductor growth markets of the present.

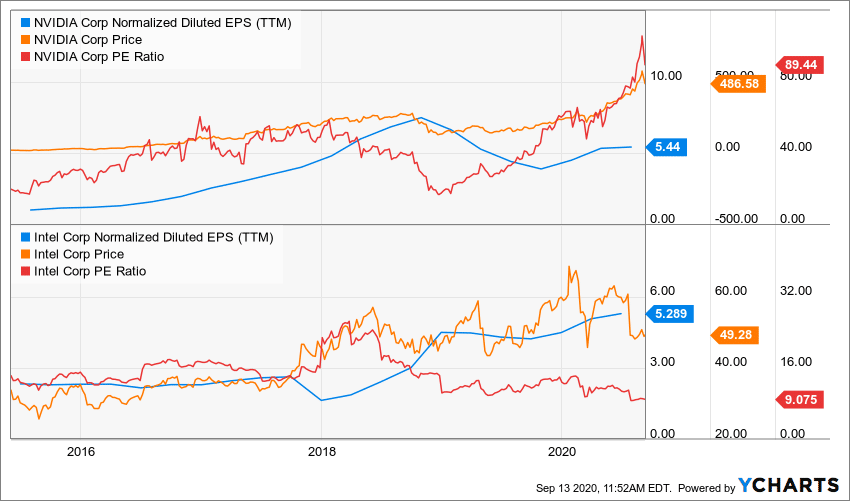

And now, let’s tie it all up in a bow by looking at the metrics themselves in absolute terms…

This may be shocking, but both Intel and Nvidia have earned the same amount of money per share over the last twelve months – around $5 and change. But Nvidia trades at 90 times that $5 at $486 per share while Intel trades at 9x, selling for just $49 per share. So if you disliked the 100% PE ratio premium of 2015, then you will absolutely despise the 1,000% premium we see today.

Now, all I’ve done is described what’s gone on during the last half-decade. What happens from here is anyone’s guess.

Can Intel all of a sudden begin out-innovating or out-executing Nvidia over the next five years? It could happen, but your fellow investors certainly don’t believe that this will be the case. Could Nvidia stumble and begin losing market share to rivals like Intel and AMD and others in various key markets? Of course they could. But again, based on current prices and multiples, almost no one else believes that this will be the situation. Could the stock market all of a sudden decide that Intel, with all of its problems, is still the better investment prospectively considering how inexpensive it is at present? This would probably require a market-wide shift in preference for value stocks versus growth stocks, but this absolutely could end up happening. It’s happened before.

And so what I want you to take away from this look back are the following points, and you ought not ever forget them:

1. Facile valuation metrics like PE ratios can be calculated by anyone, even a child, and so they are unlikely to be useful on their own in determining which investment will work out better. If it were that simple to say 15 is cheaper than 30, therefore better, then becoming a billionaire by picking stocks wouldn’t be a challenge at all. One could write a software program on a Monday and begin beating the markets by Wednesday if this were the case. Avoid rules of thumb or easy answers based on widely available numbers that anyone could glance at.

2. Value investing is the most intuitive form of investing in existence – the idea that you could buy a dollar’s worth of something for 80 cents before others have the chance to bid it back up to a dollar works great on paper. But if everyone is playing the same game, it’s harder. And if a bargain is so obvious, then surely it wouldn’t simply just exist, sitting out there in the open for all to see. There are other factors the market is considering when it produces that bargain price with its relentless buying and selling activity. Those factors frequently end up being of significantly more importance. Especially in sectors where innovation drives investor propensities.

3. The fact that two stocks in the same sector, like Intel and Nvidia, could earn the same amount of dollars per share but trade at a disparity of between 9x and 90x trailing earnings tells you that almost nothing about investing can be considered a science. How can it be anything other than an art? An art rife with subjectivity and sentimentality as all great art forms are; everything that matters being captured solely in the eyes of the beholders, those beholders unconstrained by any convention or decorum you’d like to bridle them with. You are welcome to delude yourself into thinking that you’re conducting a scientific process when selecting securities. You can build mathematical models so toweringly high that they block out the sun. But in the end, nothing you construct with numbers can withstand the thundering shifts in sentiment of the crowd galloping by. They will trample through your laboratory, upsetting your neatly ordered columns and tables, careening back and forth between greed and fear, lust and loathing, lasciviousness and restraint, daring and demurring, across unmeasurable intervals of change.

If only there were a formula. Or a rule. Or a constant. But alas, there are none. Accepting this – and choosing to play anyway – is an important step toward our maturation as investors. Everyone comes around to this truth sooner or later. Do it sooner and set yourself free.