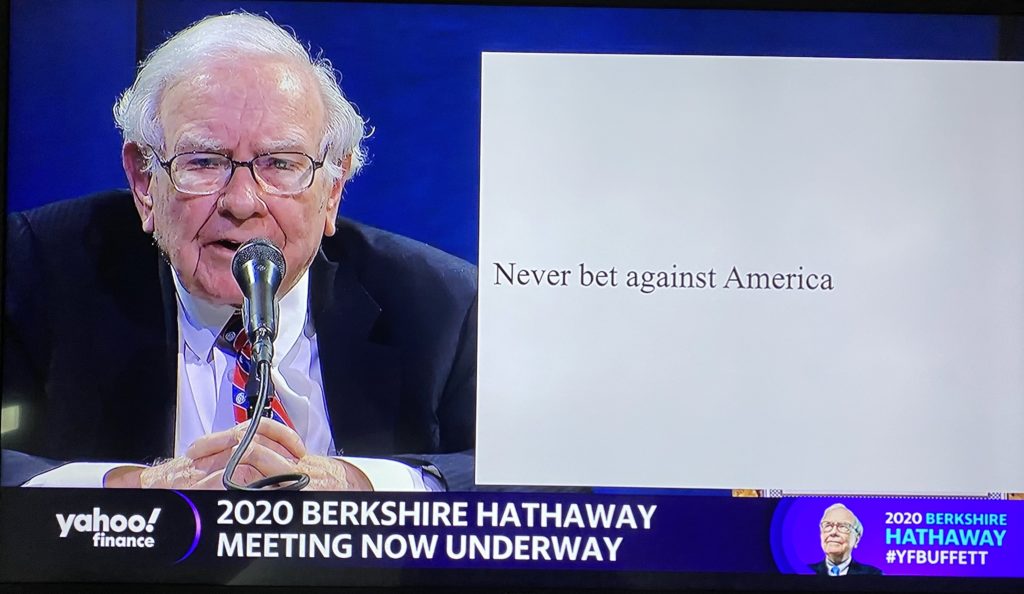

An 89 year old man who hasn’t gotten a haircut in months sits at the dais, alone, accompanied by a hotel ballroom all-purpose drinking glass filled with Coca-Cola and a stack of printed slides. The slides are text-only, black font on stark white. No frills.

The speaker is the most legendary investor and business personality in the world. His financial conquests have accrued an almost mythological tincture in their telling and retelling over the decades. He is Daedalus, having built a labyrinth of intersecting interests from insurance to electricity, and then a pair of waxen wings to fly above it all, with just a few dozen employees and contracts written on cocktail napkins. He is Midas, touching afflicted financial corporations in a time of mass insolvency with his rescue money and, more importantly, his imprimatur. One-eyed Odin sitting beneath the eaves of Yggdrasil, having paid a bodily price to have drunk from the Well of Wisdom. He is the Oracle, with tens of thousands braving the journey and the Omaha Embassy Suites to hear his annual pronouncements.

Many years from now, after Greg Abel, Ajit Jain and others have completed the shareholder value-enhancing work of dismantling the Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate, unlocking fountains of capital and geysers of cash, we will look back and ask ourselves “When did it all end?”

We haven’t quite seen the end yet, but it’s close.

We have almost undoubtedly seen the peak, which I place as the spring of 2015.

Five years ago this May. The Buffett mythos, the Warren and Charlie Show, the ‘Woodstock of Capitalism’, the theme-parking of money, the folksiness as a business model, the newspaper tossing with Bill Gates, hand gesturing with Jay-Z, lunching with Obama. Buffett’s 50th* annual letter to shareholders, released in March of 2015, was in celebration of Berkshire’s Golden Anniversary (1964-2014), the period of time he describes as the company being “under present management.” It was his best piece of writing in years, perhaps among his best shareholder letters of all time. It should be in a museum. It will be.

If 2015 was the Warren Buffett legend at the top of its power and influence, what we saw this weekend is a reminder that five more years have gone by and everyone’s gotten half a decade older.

Trump has become president and political commentary from Omaha has been almost non-existent ever since Buffett appeared on stage with Hillary during the 2016 campaign. Charlie Munger still speaks up from California, but he’s not exactly on the radar of the segment producers at Good Morning America.

Value investing, which had become synonymous with Warren Buffett because of his early association with mentor Ben Graham, has been unequivocally trounced by growth investing, the trend since 2015 having accelerated a rout that had already been underway since the end of the aught’s decade. Fortunately, Buffett isn’t actually a value investor in practice – Mastercard, Visa and Apple are growth stocks with competitive moats and burnished brands, which is what he really prizes most in his long-term stockholdings. But there are huge holdings in so-called value stocks on the books at Berkshire and they’ve contributed to a decade of underperformance versus the S&P 500 for shareholders.

So, the last few years have not been kind or particularly momentous.

Anyway, the old man spoke on Saturday. For a long time. The sparsity of text on each slide was in no way a signifier of whether or not he had much to say. Buffett was, as always, loquacious and brimming with interesting statistics – American history, market returns, inflation – turns out the Louisiana Purchase, at just 3 cents an acre, was an absolute steal.

But it wasn’t the same.

Unlike the feeling you had coming out of previous Berkshire Hathaway weekends – when risk was rewarded, long-termism was the only termism worth living and American-style capitalism would always prevail – this time, the message was not quite as crystal clear. Nor as relentlessly optimistic. You didn’t come away from this Saturday’s event humming the Rocky theme in your head.

In 1998, a previous version of Warren Buffett stood firm throughout the late summer and fall as a currency crisis in Asia worked its way through the global financial system, culminating in a lightning-sudden crash for US stocks, a massive hedge fund rescue and the devaluation of the Russian ruble. Buffett didn’t sell shit. He hung tough as his portfolio experienced a then-massive drawdown of $6 billion over 45 days. A paper loss, neither the first nor the last that he would experience throughout his career. He says temperament is more important than intelligence in this game, because everyone is intelligent enough, but not everyone can make decisions under duress. It helps that Buffett doesn’t experience the duress of a client calling him up, panicked about his retirement savings, threatening to pull his account or sue for losses. There are no clients, only shareholders of the insurance company. There are no accounts to be pulled, the money is all property and casualty insurance premiums – it comes in regardless of the “returns” being earned on it. Buffett’s temperament is probably world class – but his access to permanent, free-flowing, inbound capital hasn’t hurt either.

In 1999, a previous version of Warren Buffett tuned out the siren song of the wireless and dot com bubble, making the point that even if the futurists were right about how cell phones and the Internet would change the world (they were), it would still be nearly impossible to tell, in advance, which companies would win. In his November 1999 Fortune Magazine column, he points out the futility of having been a shareholder of the auto companies or the airlines in the early stages of their transformative growth. Almost no winners, despite their impact on the world. So he watches and waits the mania out, on the receiving end of sporadic jibes about his obsolescence as an investor from columnists, traders and the sort of parvenu McMillionaires being created on an hourly basis at the IPO mill. Buffett didn’t buy shit. He would stand tall through the ensuing burst bubble, with a dot com-free portfolio. While the dentist/daytrader class licked its wounds, he spent the post-Millennial period picking up folksy investments in carpet companies and aluminum siding plays and paint manufacturers, envisioning the coming housing boom five years before we’d begin falling in love with real estate as a new, new national pastime.

In 2008, a previous version of Warren Buffett found himself in the enviable position of being able to play White Knight to all of the great American financial brands that had lost their way. Bankers were in need of precious capital and a dollop more of that imprimatur stuff to ease the concerns of their shareholders, employees, counter-parties and regulators. Buffett conducted these crisis-era refinancing rescues like movements in a symphony. The phone was ringing and Buffett was one of the few people writing checks – checks that came dusted in a golden sheen of respectability. Goldman got one, General Electric got one, Bank of America got one too. They got cash today, plus the pixie dust, plus the option of having the debt obligation converted into new shares of stock rather than having to be paid back. It was win-win-win. The companies won because their share prices recovered, the government won because it was one more set of checks they wouldn’t have to write themselves out of TARP or TALF or pull from elsewhere in the alphabet stew of bailout programs. And Warren Buffett won because he named his terms on the current income his preferred shares earned, named the strike price at which they’d convert to equity, and named the timeframe for conversion. And they thanked him profusely for doing so.

High up in any listed iconography of Berkshirism would be Buffett’s October 2008 op-ed “Buy American. I am.” Despite the fact that it came out six months before the actual stock market bottom and nearly two whole months before the Bernie Madoff revelation, it still resonated deeply with the beleaguered Boomer investor, for whom seeing the Buffett Banner waving above the fray was still meaningful, something to reach for and cling to amid the bloodbath. Buffett told readers of the New York Times that morning (emphasis mine),

“So … I’ve been buying American stocks. This is my personal account I’m talking about, in which I previously owned nothing but United States government bonds. If prices keep looking attractive, my non-Berkshire net worth will soon be 100 percent in United States equities. Why? A simple rule dictates my buying: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful….Equities will almost certainly outperform cash over the next decade, probably by a substantial degree. Those investors who cling now to cash are betting they can efficiently time their move away from it later. In waiting for the comfort of good news, they are ignoring Wayne Gretzky’s advice: “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not to where it has been.”

Compare this statement with the souvenir pearl that investors came away from this weekend with; as Andrew Ross Sorkin points out, “Warren Buffett said the $137 billion he had on hand ‘isn’t all that huge when you think about worst-case possibilities.’ Let that seep in.”

It has seeped in.

Late Friday night we learned that Buffett spent the late March and April period liquidating his holdings in the four major airlines, companies in which he’d been the largest shareholder for years – and at significantly higher prices. “The world has changed,” Buffett explained to Becky Quick during the Q&A. There was nothing particularly poetic or insightful about his defenestration of the airline stocks, just a guy taking huge losses at or near the bottom of an investment gone wrong. To Buffett’s credit, he didn’t dance around the facts of these multi-billion dollar losses, nor seek to assign blame elsewhere, nor get overly cute in the denouement. He just said he made a mistake.

In contrast to the previous versions of Warren Buffett, this version spoke in a raspy voice, with long and frequent pauses**, in an empty room absent applause, laughter or the sort of twinkling eyes and vigorous head-nodding that the Shareholder-in-Chief must have grown accustomed to over the years. This version sat alone, speaking into a camera lens, guiding the live viewers on Yahoo Finance through a mostly mirthless and lethargic power point exercise that strained the endurance of even the most committed Buffettologist or Berkshire acolyte (like myself).

Watching a man who’s already given the world so much literally will himself through hours and hours of this at almost 90 years old was pretty tough. As if he owes us anything more than he’s already said and done. As if he didn’t want to disappoint, despite the disappointment that is our current situation.

The version of Warren Buffett we got this weekend has been bruised by the bank stocks and battered by the airlines. He’s had the joy of being among his live audience and fellow shareholders taken away from him (hopefully just temporarily). There was no newspaper tossing. There was no cocktail party at Borsheim’s Fine Jewelry. No bonhomie at the Nebraska Furniture Mart. No steak dinner at Gorat’s. Just a stack of papers with sentence fragments and bullet points on them, and a decidedly non-triumphant conclusion that now is maybe the time to buy stocks…but maybe not? Imagine seeing Bruce in concert but he doesn’t much feel like doing Born or My Hometown that night. Imagine a Picasso exhibition, but it’s his sketches, not a painting in sight.

A Berkshire meeting without the meeting, a pep rally for investors but the rallying cry is “I don’t know, perhaps not yet.” Berkshire Hathaway as a quasi-religious institution for capitalists just fading away like this…it’s so anti-climactic. Unsettling. The fastest bear market panic in history and St. Warren was a seller, not a buyer. No “one last big score” bravado. No talk of “we’re reloading the elephant gun.” No mention of great opportunities having been created by the latest crisis. No kneejerk greediness while others are fearful. Just a shrug, the meeting was essentially a five-hour caveat.

“We’ll see,” says the Oracle, to the delight and relief of absolutely no one.

*At first, he didn’t sign them himself. Warren Buffett wasn’t exactly WARREN BUFFETT in the mid-1960’s.

**We’ll see if I can do anything other than rasp and pause at the age of 80, let alone 90. It’s not looking likely 😉

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 95017 additional Info to that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here on that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: thereformedbroker.com/2020/05/04/this-version-of-warren-buffett/ […]