Over the weekend, everyone was sharing this New York Times piece about what’s happened to Mount Everest. It’s become more crowded than Disneyland. Hundreds of climbers making camp and trudging toward the summit, nearly a dozen deaths this year as a result.

Climbers were pushing and shoving to take selfies. The flat part of the summit, which he estimated at about the size of two Ping-Pong tables, was packed with 15 or 20 people. To get up there, he had to wait hours in a line, chest to chest, one puffy jacket after the next, on an icy, rocky ridge with a several-thousand foot drop.

He even had to step around the body of a woman who had just died.

“It was scary,” he said by telephone from Kathmandu, Nepal, where he was resting in a hotel room. “It was like a zoo.”

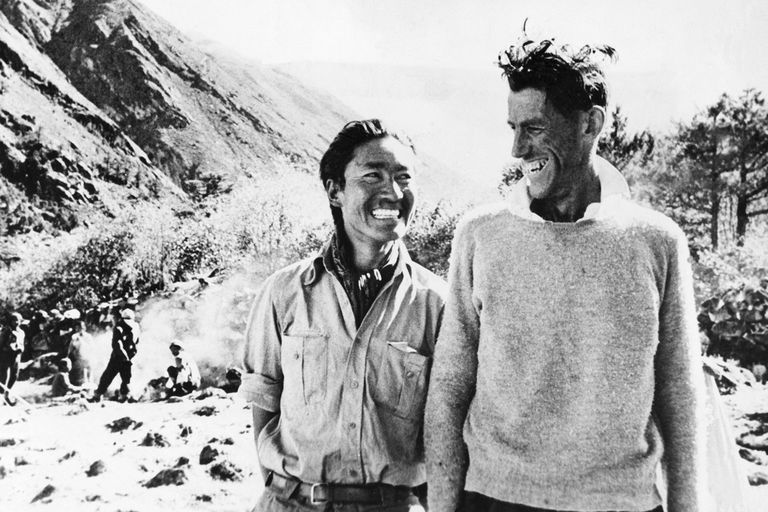

This picture tells you everything you need to know about the current conditions there:

In case the obvious metaphor is lost on you, here are the very first people to have reached the summit of the highest peak on earth – explorer Sir Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay:

It should go without saying that when Norgay and Hillary ascended to the top in 1953, they made history. Schoolchildren learned their names (or, at least Hillary’s name) for decades after.

This feat went into the annals of human exploration achievement, along with the moon landing, the discovery of America, the first transatlantic flight and Magellan’s circumnavigation around the globe. And now, it’s a selfie. An Instagram post. A Facebook Moment.

What happened?

People didn’t suddenly become more brave in great numbers. The mountain’s trails didn’t suddenly become less steep or daunting. The oxygen and extreme temperature situation didn’t spontaneously moderate.

What happened was a slow but steady amount of progress in the technology and equipment needed to make the climb, thus opening the way for more and more people to attempt it. Lots of money thrown at a problem – getting to the top – that seventy years was only being dared by a handful of would-be summiteers. And when lots of money is thrown at a problem, and the technology becomes widely available to the masses, the opportunity is gone.

Climbing Mount Everest still has cache, of course, but compared to ten years ago? Or 30 years ago? Not really.

The rewards are there for being early and breaking through before the rest of the crowd. The rewards for coming later, when the risk is less severe and the tools are more widespread and easily adopted, are significantly diminished.

We see this phenomenon play out in the investment markets all the time, just as it does in the somewhat related world of private business investment.

The first people (and dollars) to discover something exploitable and profitable are treated better than the subsequent dollars that come rushing in. The imitators then ruin the endeavor for everyone, bringing with them throngs of human bodies and enough capital to crowd out whatever profit margins once existed. Valuations are pushed up, secrets are shared, shoddiness and sloppiness appear everywhere as the worst, most amateurish entrants are attracted, gold rush-like, onto the field. Scam artists aren’t far behind, followed by new regulations to rein everyone in once enough money has been lost, stolen or set on fire.

And before you know it, what was once a lush and bountiful opportunity for the few, becomes an endless chain of mouth-breathing nobodies pushing each other off the side of a mountain for their own fleeting moment of opportunity in the sun. And then everyone loses.

This has happened in stock picking, as Greenwich Associates founder Charley Ellis has been saying for years. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, there were hundreds of professionals running a thousand or so investment funds, with a wide open opportunity to generate alpha and the endless mistakes of mom & pop plungers littering the ground before them – easily harvestable mistakes for the pro to carry away. Alpha was more attainable, and with more regularity, just by being pretty good. And lots of money was made. This sent the MBA factories into overdrive and within a generation, the hundreds of fund managers swelled to thousands. A trillion dollars came flooding in thanks to the rise of the 401(k) retirement plan. Armies of computer literate analysts and rapid-fire traders came into the game. Hundreds of thousands of US participants and then hundreds of thousands from around the world.

Alpha became scarce, and then, in the aggregate, non-existent. Schemes and tactics that used to result in 300 or 400 basis points of outperformance a year were arbitraged away by computer. Not only did the game change (thanks to new regulations prohibiting the selective dissemination of material information about companies), but all of the players saw their skill levels rise at the same time. So now it’s harder and everyone playing is better, stronger, faster, more educated and equipped with a quantity of computing power that was once reserved for rocket flights to the moon.

And you wonder where the alpha went. And you listen to people saying “it’s cyclical, active managers will make a comeback” and you ask yourself “What world is this person living in?” Technological change doesn’t reverse itself just because it would make everyone feel better.

According to a16z, there are now 700,000 podcasts available and thousands more launching every week. You have any idea how good you have to be to get a following now? Ten years ago, you could be anybody and just hang your shingle. Some of the biggest podcasts around today would never have been able to build an audience were they to launch right now. And that’s okay. Good for them – they took a risk and tried something before it became obvious that what they were doing would ever become something meaningful.

There are now hundreds of music festivals. They used to take place during the three months of summer but now they are year-round, a dozen at least, every month. There are so many that the organizers of Woodstock Fifty, the commemorative concert for the original music festival, can barely get enough media attention and cultural oxygen to survive. There are so many craft beers on the market that the Boston Beer Company’s Sam Adams brew – the original that defined the genre – is almost an afterthought at this point in time.

This is what crowds do to opportunities. No matter how good you are, if what you’re doing is very profitable, others will copy you and will be “good enough” to impinge on your game. Which is why the best investments are those with moats – companies that are so good at something that their abilities and assets literally act as a barrier to those who would follow and imitate. These competitive advantages you build won’t necessarily keep crowds off the mountain trail, but if you can build them to be formidable enough, they should dissuade enough of the horde to follow other trails elsewhere.

And if you find yourself doing things just because the whole crowd around you is doing them, it may feel safe at the present time, but over the long-term, that safety is not going to yield anything more than the mediocre results everyone else in the crowd will be topping out at. Being special requires taking a risk and doing something unproven – and difficult – before it becomes just another selfie opportunity for everyone else.

Thank you for every other informative blog.