The history of Wall Street wealth management as we know it today starts during the ramp up to World War I.

The Defense Department needed a enormous source of funds and they decided that US war bonds were the best way to go – but how to sell them? That’s when the relatively obscure denizens of Wall and Broad were first introduced to America. Brokerage firms sent armies of salesmen across the country to sell Main Street on the idea of patriotism and dependable income. They primarily sold bonds in denominations of $100. The income was tax-free and, remarkably, the investment houses were selling them at no commission. The Street’s dealers essentially used them as a loss-leader to open new customer accounts.

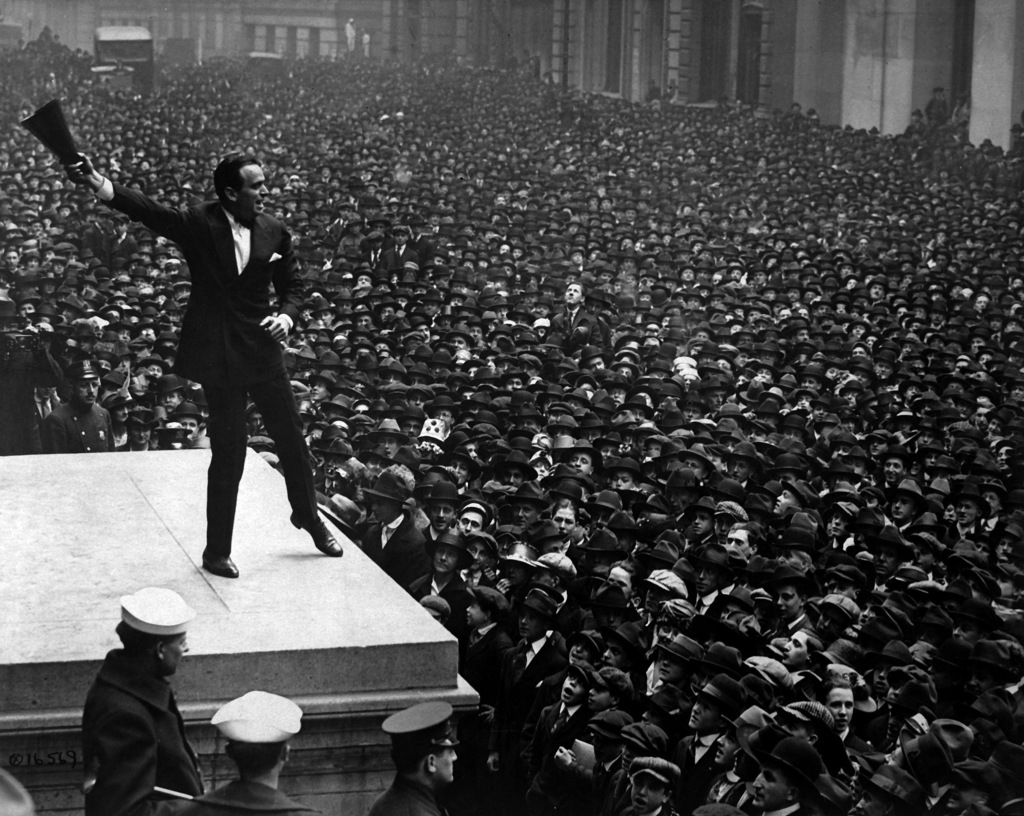

And boy did it work! The people they were selling to had never transacted with them before but now they had become “clients” overnight. By 1917, it is estimated that some 350,000 Americans had taken part in this Liberty Loans program – but by the end of 1919 the customer base had swelled to over 11 million. According to the Wall Street historian Charles Geisst, this was the first time millions of ordinary people had ever bought an “intangible” or held a paper investment. “Inadvertently, the war effort had given the vast majority of small investors their first taste for securities that would only grow stronger.”

(Movie star Douglas Fairbanks rallies a crowd of war bond investors in front of New York City’s Sub-Treasury Building, April 1918)

You already know what happens next – the US and its allies win the war and the Treasury pays back both principal and interest on the maturing Liberty Loan bonds. All of a sudden, Wall Street realizes it has tens of millions of new customers who now have accounts that are flush with this newly returned cash. So do they send that cash back? Hell no! It all ends up being plowed into the corporate bond and stock market, creating a boom for the ages throughout the entire the next decade. The original brokers to Main Street – who began as ad hoc war bond salesmen – were now the gatekeepers for this torrent of investor cash, buying into stocks, closed-end funds and other trading pools with huge sums of unsophisticated money.

That right there is the story of how Wall Street and Main Street first came together. And for 90 years, it was a seller-buyer marketplace – one party held all of the information and used that advantage to sell to the other party. The Street was regulated and the consumer was protected – to varying degrees over the years – but there was always an information asymmetry and the conflicts of interest were simply enormous.

This basic structure of financial product salesmen catering to a nation of know-nothings began to change in the 1970’s when Charles Schwab opened up shop in San Francisco – a million miles away from the Wall Street wirehouse establishment – with a walk-in office and a bank of phone operators. Schwab offered its customers the access to investment markets they’d never been able to get directly on their own. The Internet would amplify this access tenfold just twenty years later. The explosion of available information and alternate routes to execute trades was another giant leap forward. The latest disruption to the traditional gatekeepers began sometime in the middle of the last decade when, armed with an arsenal of web-enabled tools and a better customer care proposition, the Registered Investment Advisor (RIA) complex began to see its assets under management explode. Fee-based advisory began ripping chunks out of the large, unwieldy brokerage firms and the incumbents didn’t do themselves or their reputations any favors by blowing up during the financial crisis. By the time the dust had settled, the market share of the wirehouse wealth managers had shrunk to under 50% for the first time ever – since the beginning in WWI.

Today, there are 11,000 investment advisory firms holding themselves out to the public, from broker-dealers to RIAs to insurance salesmen to bank branch counselors to CPAs. The industry has a veritable rainbow of professional designations and investment strategies and standards of care and regulatory oversight. Main Street’s investor class is completely and utterly baffled about who does what, who gets paid how and what makes sense in which scenario. The American public has $67 trillion in financial assets and roughly $13 trillion of it is invested in stocks, mutual funds and corporate bonds. This $13 trillion excludes the assets currently held in bank accounts, pensions funds, qualified retirement plans and the like, which takes it substantially higher.

In an environment like this, firms with a compelling message and a fair value proposition can take a ton of share from firms that are hopelessly conflicted and clinging to the bigness of their brand. By now, you’re all familiar with the traditional way of doing things: Hidden fees, overly complicated strategies, conflict-as-a-business-model, a sales-first culture of pitching and closing and an incidental advice model wherein suitability was “good enough” while quantity of commissions was more important than quality of care. That was then, and it’s not going to work anymore.

Firms that emphasize transparency and education can set themselves apart. We can be heroes.

In my opinion, a firm with educated clients is going to be better off than a firm that’s gotten by on mystique and subterfuge. At my shop, we try really hard to explain everything we’re doing on their behalf and to remove as much of the mystery of the investment process as we can. We go out of our way to educate in a variety of ways:

* Two monthly letters covering the big picture and the mechanics of our portfolios

* A quarterly conference call open to all clients of the firm

* daily online access to performance reporting and financial plan progress

* Multiple on staff CFPs to conduct regularly scheduled portfolio reviews and field questions any time of day

* Daily blogging on multiple platforms, covering topics from markets to economics, planning to investment strategy

And while that may seem like overkill, or this level of openness may be shocking to entrenched Wall Street firms, we wouldn’t have it any other way. We believe that an educated client becomes a better client and has a better chance at riding out the tough times because of this elevated level of understanding. We believe that an educated client becomes more appreciative of our efforts to help them and therefore becomes more engaged. We believe an educated client has more longevity than a client who spends their time wondering what’s going on.

The Information Age has come to the wealth management business. Those who make it a practice to share information rather than withhold it are going to win.

“@ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/E86PyJXOVF” <- under appreciated, high value proposition is education. Well said.

RT @ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/cXQL5PGLHD

RT @ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/cXQL5PGLHD

RT @ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/cXQL5PGLHD

We educate our clients because it’s fun, and because that’s the way it should be. http://t.co/uvniPjVlpj @ReformedBroker

Why We Educate Our Clients. http://t.co/AbsbBBskl4

RT @ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/lxvIj8Mx7i

Why We Educate Our Clients by @ReformedBroker http://t.co/n8OORd8Uys

Josh on why educating our clients is so important to us…

Why We Educate Our Clients by @ReformedBroker http://t.co/8Gp2jwXsST

Why We Educate Our Clients http://t.co/KzpkPfc3Uv

Really cool story on how this all started RT @ReformedBroker: WHY WE EDUCATE OUR CLIENTS http://t.co/rXJV5wQqDm

[…] Why We Educate Our Clients (TRB) […]

RT @ReformedBroker: Why We Educate Our Clients http://t.co/svrL7tN8WX

RT @ReformedBroker: Why We Educate Our Clients http://t.co/svrL7tN8WX

RT @ReformedBroker: Why We Educate Our Clients http://t.co/svrL7tN8WX