This weekend, thousands of institutional investors, financial advisors and wealth managers are faced with one of the most uncomfortable questions imaginable:

Do we need to fire Pimco?

Pimco’s flagship fund, Total Return, can be found in allocations everywhere. From pensions to endowments, from 401(k) sponsors to retirement plans, in the accounts of private investors and insurance companies, wirehouse FAs, bank branch brokers, RIAs – Total Return is ubiquitous. It’s got one of the only mutual fund ticker symbols that brokers call out as though it were a stock, as in “Why don’t you just buy the guy some P-Tax”, a shorthand for PTTAX, the call letters of the fund’s A class shares. As the second largest bond fund on earth and largest active one, it’s also extraordinarily widely held, and this is why the news of Bill Gross leaving the firm (or being pushed out) is such a huge story for the industry.

How did Pimco Total Return get so entrenched in the first place?

Our story begins, as it often will, with an amazing track record of outperformance. Put simply, whatever Pimco was doing, for a long time, was working. A potent mixture of market-beating returns, marketing savvy, intellectual leadership for the industry and outsized personality fostered a devotion to the firm and its best-known product. The cult of personality surrounding Bill Gross is unlike anything we’ve seen in this industry since the heydays of Peter Lynch and Bill Miller. The bond fund and its manager have been sold to clients with impunity for two decades. Pimco Total Return has become the IBM of mutual funds, in that “No one ever gets fired” for recommending it.

This reliance on Pimco on the part of asset allocators worked very well for years, and, as a result, it became a standard inclusion into portfolios around the world. The regular investor letters and commentaries from Mr. Gross kept professionals up to date with their designated manager’s ongoing take on the markets and the economy. The ubiquity of Mr. Gross in the media was reassuring for the retail investor and more casual shareholders who were invested through a retirement account somewhere. And once the Harvard endowment’s Mohamed El-Erian re-joined in 2007 to become the second face of the firm, it was almost a fait accompli that Pimco would become gigantic.

The system worked perfectly – Gross would make wagers on the bond markets and interest rate curves while always having something clever or insightful to say about it publicly. And so long as he was delivering an annual return near or slightly above the benchmark Aggregate Bond Index, the money kept rolling in. Gross delivered a 13% total return in 2000, a year during which the Boomers experienced the first real stock market losses of their adult lives. During the next five years, he delivered above-index returns and cemented the franchise’s industry dominance. Pimco’s orders had grown so large that the Wall Street desks who executed them began to refer to the firm as The Beach, as in, “The Beach wants another $16 million in 5-year swaps at one-spot-nine-three.”

So what happened?

In hindsight, of course, the first crack in the Pimco story becomes a glaring one when we look back at it.

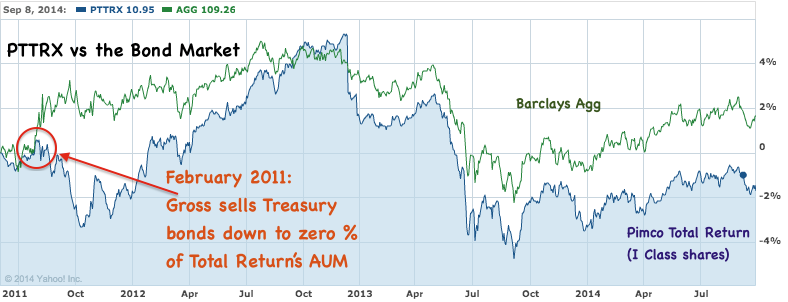

In February of 2011, Gross loudly proclaimed his newest big bet to anyone who would listen: Pimco Total Return had taken its allocation to US Treasury bonds down to zero. As recently as the previous December, Pimco Total Return had been carrying as much as 22 percent of its AUM in Treasurys, so this was a radical shift for such a large fund. Gross compounded the move by being extremely vocal about his rationale – he went so far as to call Treasury bonds a “robbery” of investors given their ultra-low interest rates and the potential for inflation. He talked about the need for investors to “exorcise” US bonds from their portfolios, as though the asset class itself was demonic. He called investors in Treasury bonds “frogs being cooked alive in a pot.” The rhetoric was every bit as bold as the fund’s positioning.

It’s really hard to pound the table like this and then be flexible in the aftermath when evidence to contrary begins to surface. Once the market starts to go against a famous manager, and he’s become associated with the wrong trade so publicly, there’s a obvious temptation to dig in deeper or to hunker down. To throw people out of one’s office when they voice dissension. To view the movement of the market as an affront to one’s intelligence or as a debate adversary that must be talked out of its obvious wrongness. For a private investor, this mindset can be dangerous, but for a highly-visible professional investor becomes utterly debilitating. And in 2011, no one was more visible on the rate question than Bill Gross.

Or more wrong.

Gross’s directional bet on bond yields going higher and bond prices going lower was a disaster. In fact, the exact opposite of what he had called for is what ended up happening. Treasury bond yields plummeted from that February 2011 flag-planting moment. Yields on the 10-year Treasury bond had dropped from an earlier year high of 3.75 percent to as low as 2 percent in the summer. By August, Bill Gross was forced to defend himself in public. He admitted to the Wall Street Journal that he had been “losing sleep” over the bet. He called it a “mistake” in the Financial Times a few days later. By that point in the year, Pimco Total Return had underperformed 84 percent of its peers. For the first time in a long time, the Bond King of Newport Beach had begun to look extremely fallible.

This moment is captured in the chart I made below:

As you can see, Total Return has pretty much never recovered from this bet, with the brief exception of a fleeting moment in the fourth quarter of 2012. In 2013, Total Return had its worst year ever, a negative 2 percent return, which trailed the performance of nearly three quarters of its peers.

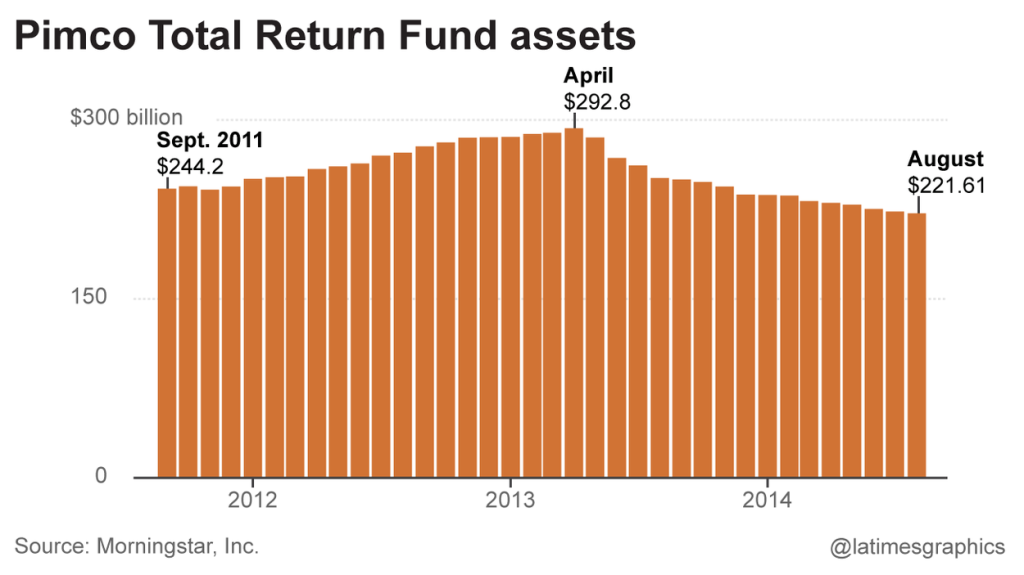

Since the Taper Tantrum last spring, things have gotten tougher for the bond management business in general, but the bleeding of this fund has been especially pronounced: Some $70 billion in net outflows have left Pimco Total Return since its peak AUM of $293 billion in April of 2013. As performance suffered and rate fears began to take hold, the outflows at Pimco Total Return began last spring – and they never stopped.

See the below chart from the LA Times:

Finger-pointing is the constant companion of outflows in this industry. Lower AUM means smaller bonuses which mean stressful conversations at home and belt-tightening at work. Everyone at an investment organization is miserable when this cycle begins, everybody feels it. That’s when the in-fighting begins and stress fractures within a culture start to show.

Rumors of tensions within the firm began to make their way into the press and it became harder to sort out which were true and which were exaggerations. In February of 2014, things came to a head when the Wall Street Journal’s Gregory Zuckerman and Kirsten Grind ripped the facade away and put out an extensively-sourced piece about the personality clashes within the firm. These arguments over strategy and communication had chased out El-Erian and turned Bill Gross into a sort of King Lear figure within the company. For the first time ever, we were hearing specific snippets of dialog from within the firm and it wasn’t pretty:

“I have a 41-year track record of investing excellence,” Mr. Gross told Mr. El-Erian, according to the two witnesses. “What do you have?”

“I’m tired of cleaning up your s—,” Mr. El-Erian responded, referring to conduct by Mr. Gross that he felt was hurting Pimco, these two people recall.

For investors who had assumed Pimco’s stewardship was rock-solid and its process was unimpeachable, this was a wake-up call. All of a sudden, the $1.9 trillion asset manager looked vulnerable and human. The psychological impact this revelation had on the investing public cannot be overemphasized. Faith in a manager, once shaken, becomes as fragile as any belief system in the presence of too much scrutiny.

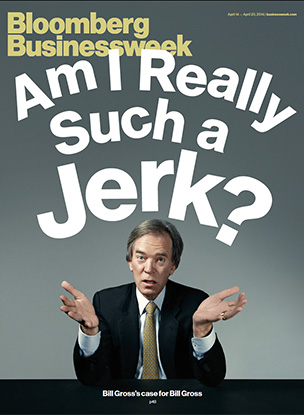

Bill Gross’s appearances began to take on an almost performance-art caliber of surrealism. By this time things had come to a head internally in the wake of El-Erian’s departure. The bleeding from Pimco continued. BusinessWeek’s cartoonish Bill Gross cover this April, along with the bizarre keynote speech he did while wearing sunglasses at June’s Morningstar conference were the final straws (see below):

BusinessWeek, April 2014

Bill Gross deliver his keynote speech at this summer’s Morningstar Conference in Chicago

Advisors who had been (reluctantly) recommending the fund company to their clients and telling people to “stay the course” finally had the excuse to hit the sell button. Firing a manager is extremely difficult for financial intermediaries to justify, the longer that manager has been a part of the recommended strategy the harder it is to do an about-face. But turmoil at the top or a change in PM almost always gives advisors the cover they need to make a change while maintaining the guise of discipline. “Mr. Jones, as you know, we are long-term oriented, patient investors most of the time. However…”

It’s been estimated by Morningstar and others that the events of this past week will lead to Pimco outflows on the order of 15 to 30 percent of the firm’s total assets. Some of the money is expected to follow Bill Gross to his new unconstrained bond fund at Janus. Jeffrey Gundlach’s Total Return product at DoubleLine should also get a big bump, as advisors trade one cult for another and assure their people that Jeff is the real Bond King, the one who got the post-crash period right and with a smaller, more agile fund to boot.

But I think a lot of this fleeing cash will find its way to Vanguard (home of the world’s largest bond fund) or to the iShares / State Street cohort of fixed income index funds. Increasingly, investors will reach the conclusion that whatever alpha a manager may generate, it’s not worth the potential drama.

By recommending a bond manager, even a bond king, asset allocators are inherently putting their stamp of approval on that manager, come what may. And while firing a manager is not the end of the world, there is a limit to how many times you can actually do it. How many times can you call a client and repudiate your own fund picks before the client begins to second guess your expertise? Believe it or not, billions of dollars are currently allocated to bad funds or products because of the very “agency problem” I’ve laid out here. With a bond index fund, this issue goes away immediately.

Many investors will opt to do nothing of course. They’ll point to the new CIO and manager of Total Return, Daniel Ivascyn, and the depth of Pimco’s bench as reasons to stay. “The worst is over and finally the firm can focus on performance again with Gross out of the picture.” They may end up being rewarded for this loyalty in terms of future performance, even if they have to go to great lengths to justify sticking around in the near-term. They may be pilloried for neglectfulness and fired by their clients should the fund continue to falter. Anything can happen.

And so the question of “Do we have to fire Pimco?” will be the predominant topic at financial firms across the country and around the world. Virtually no large pool of assets in this industry is completely Pimco-free, whether we’re talking about Total Return or any of their other funds and SMAs. The issue cannot be ignored because the end-customers of these investors will have read plenty on the topic this weekend and will have questions and concerns of their own. No amount of reassurance from Pimco can change this fact right now.

This is the item that will lead off almost every investment committee meeting on earth tomorrow.

RT @lenwelter: Great write up by @reformedbroker on Pimco – “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/PquzxuaI3s

RT @ReformedBroker: “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/HNoxXZf4NP

[…] For some good analysis of the thinking investment managers are going through, as they consider pulling cash out of PIMCO, read Josh Brown’s analysis here. […]

“Do we need to fire Pimco?” | x-post /r/businesshub http://t.co/fFQM3j5CZ2

RT @ReformedBroker: “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/X8Ulqv6lQL

[…] For some good analysis of the thinking investment managers are going through, as they consider pulling cash out of PIMCO, read Josh Brown’s analysis here. […]

RT @GEJohnsonII: The best article on the Bill Gross situation. http://t.co/SaX8eAUZZr

[…] a great piece over the weekend Josh Brown goes into some detail on the situation with Bill Gross leaving PIMCO. He asks the important question […]

[…] For some good analysis of the thinking investment managers are going through, as they consider pulling cash out of PIMCO, read Josh Brown’s analysis here. […]

Something I used to do. “@YahooFinance: “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/TVEZ2jinkf via @ReformedBroker http://t.co/RL72M1PRd1“

RT @YahooFinance: “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/rK1k76hG9O via @ReformedBroker http://t.co/4R2r7ZkUSd

RT @YahooFinance: “Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/rK1k76hG9O via @ReformedBroker http://t.co/4R2r7ZkUSd

““Do we need to fire Pimco?” by @ReformedBroker http://t.co/JhcNTtVDk6” Really nice history of the PTR story

[…] “Do we need to fire Pimco?” (TRB) see also How Bill Gross and Pimco got too big for each other (LA Times) • Americans have been […]

“Do we need to fire Pimco?” http://t.co/TFIcWJyf6a via @feedly